Anchors away

Seven Canadian broadcast journalists talk about why flew the coop and went south. But it’s not just the money — honestly. They love it there.

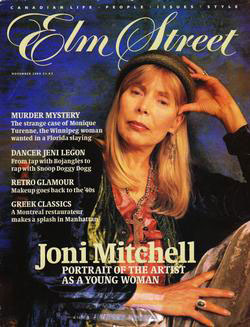

Elm Street, May 1997

The best Canadian television news talent isn’t here in Canada. It’s in London. And Cyprus. And Bosnia. And New York and Hong Kong and Moscow, working for American TV networks. Every Canadian knows the US network stars who learned their craft north of the 49th parallel: Morley Safer, Robert MacNeil, Peter Jennings. Throughout TV’s almost 60 years on the North American continent, broadcasters from Canada have regularly migrated south to bigger salaries and organizations.

In the 1980s, Peter Mansbridge was celebrated for not doing that. He resisted the blandishments of CBS, choosing instead to keep working for CBC. But Mansbridge’s decision to stay right here in Canada was an anomaly; usually those journalists offered anything that even smells like a spot with an American news outfit pursue it right away. Indeed, the recent exodus of journalists from Canada makes Mansbridge’s decision look even stranger.

In Canada, CBC is still our main television news source. Though CTV works hard to keep up, it doesn’t have as much money, as many people or as extensive a web of correspondents, producers and personnel. That is changing, of course; CBC is slicing budgets and cutting staff, and TV news has always been one of the biggest single chunks of its budget. Each time an employee announces an offer for more money from someplace else — an offer the corporation knows it can’t possibly match — what can a manager do but shake the person’s hand, wish them good luck and then heave a grateful sigh once they’re out of the building: Phew, it’s one less buyout; and it’s one less troublesome reassignment or layoff.

The exodus seems to be speeding up. As CBC shrinks, the US market is burgeoning. CNN keeps growing, extending its brand with initiatives such as its financial news channel, CNNfn, and its new sports news operation affiliated with Sports Illustrated (CNNSI). NBC and Microsoft are staking turf on the channel changer and the World Wide Web with a joint 24-hour news service, MSNBC (up and running since mid-July). Rupert Murdoch’s 24-hour Fox news channel promises a rightward tilt to balance what Murdoch sees as a leftist bias elsewhere. ABC was gearing up for yet more round-the-clock news, but shelved its channel when its new owners at Disney decided the service would cost too much money. (But shelved doesn’t mean scrapped; ABC says that the plan remains viable, just not right now.)

All of this helps to explain an increasingly common experience for Canadian viewers: seeing a familiar and trusted correspondent or anchor suddenly disappear from the map — no explanation, no fanfare, just gone — only to resurface months, weeks or even days later on an American news broadcast: ABC, CBS, NBC or CNN.

We polled seven recent TV emigrants and found that their reasons for leaving Canada were different; their conflicted feelings about their former Canadian employers often similar, and their observations about the main differences between the US and Canada to be pointed, insightful and thought-provoking.

HILARY BROWN. When Hilary Brown came to anchor CBC Toronto’s supper-hour newscast in 1984, she’d already proved her reporting credentials with 11 years of assignments for ABC News on every continent except Australia. For many with such a track record, an anchor desk might seem a more comfortable place than a free-fire zone to run out the career clock, but talking to Brown now at her base in Cyprus (she also works from London), it’s clear she prefers her current slot with ABC, where she’s been since late 1992.

She describes her itinerary for 1995: “New York and Switzerland in January. I was in Burma doing a documentary for Nightline in February and March. I was in Vietnam in April for the 20th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, Bosnia in May, June and again in July, Turkey in August, back in Bosnia in September, Greenland in October doing a crazy feature on the world’s first Santa Claus summit, and Mali doing a feature on stolen art in sub-Saharan Africa. Then, in December, I was in the Middle East, doing the hand-over to Palestinian self-rule. What a year, huh? That’s the kind of mobility you have.

“Canadians are very good broadcast journalists; they’re among the best in the world,” she adds. “The Americans recognize that and they go for it. They don’t mind if you’re Canadian, where the reverse is rarely true. I would encourage anybody I thought was good to join a US network. They’ll have a longer career and more opportunity. It’s just a fact of life.”

Brown misses Toronto terribly, but doubts she’ll return — unless she could cut a deal with ABC that would allow her six months on and six months off. But the relentlessness of the news makes that unlikely. “I don’t think I’d be able to pull that off,” she says. “The setup I have is pretty good. I’m pretty good.”

GILLIAN FINDLAY. After three years at CBC’s London bureau following Toronto-based stints at The Journal and The National, Gillian Findlay moved to Moscow and ABC News. She’s been covering the faltering first steps of Russia’s fledgling democracy, the war in Chechnya, Russian elections and President Boris Yeltsin’s health.

Her move to ABC followed several years of overtures from the network, which first noticed her while she was reporting for CBC from South Africa on Nelson Mandela’s release from prison. “They first approached me when I was still working in Toronto for The National, and wanted to know if I’d be interested in going to Berlin for them. I decided against it.” CBC offered a slot on its investigative weekly show the fifth estate as an inducement to remain. That lasted for six months before Findlay’s move to London. “I still believe that was the right decision,” she says. “There was a whole lot I learned at CBC; ABC would call me occasionally. I didn’t ever close the door on them. I just said: ‘Very nice, but not right now.”‘

She finally relented in 1994, after a lot of soul-searching: “You spend an extraordinary amount of time thinking, ‘Is this being unpatriotic?’ It takes most Canadians a while to get used to the idea. They were interested in finding women to go overseas, and a number of Canadian correspondents were approached on that basis. I had been warned that this was going to be difficult, that it would take time to get used to the system. Frankly, I didn’t find it that much different — maybe that’s just me and the story I was on.”

Findlay had also been warned there’d be less appetite for international coverage at an American network. She didn’t find that true either, noting it’s also becoming tougher to get foreign stories on Canadian newscasts. Findlay speaks with admiration of her CBC colleagues in Moscow, who produce more coverage with one-third the resources that ABC has. “When I phone up and say, ‘I’m the ABC correspondent,’ that opens doors. The process is made easier by belonging to a bigger, wealthier company.”

Asked about the possibility of her returning to Canada someday, Findlay says, “I’m not very good at living life in the long term. I know I want to live in Canada at some point. I would like to think I would be employed by somebody there. I also have fond memories of CBC and like most people who’ve worked there, I have a real commitment to it. But I’m taking this one year at a time. And whether that CBC will ever exist again, I don’t know. I’m thoroughly enjoying what I’m doing and who I’m working for, and 1 quite honestly don’t have any huge regrets about making the decision — no regrets.”

KEVIN NEWMAN. Kevin Newman, now co-anchor of Good Morning America Sunday and an ABC News correspondent, used to be the male counterpart of Thalia Assuras on the overnight shift at World News Now. Before going to ABC, Newman was happily anchoring CBC’s Midday with Tina Srebotnjak in Toronto. But that was before CBC began wooing Vancouver-based CBC reporter Ian Hanomansing to take over Newman’s position — even though Hanomansing refused to leave the West Coast. Newman said he’d rather leave than fill a chair he was going to be asked to vacate. CBC then promised Newman they would find him something at The National. Two months later, there was still no offer on the table.

Then, one morning, Newman’s voice mail at work was beeping: “This is ABC News in New York. I have a tape in front of me — how did I get this tape? Give me a call.” Newman still doesn’t know how they got that tape. Despite his uncertain future with CBC, he hadn’t been looking elsewhere. “I am one of those gushy Canadians. I could step off a plane anywhere in the country and know my way around; that familiarity was very comfortable.”

When Newman told CBC he’d had an offer from the US, management presented him with several options. Newman decided to go with the ABC challenge.

Now, Newman is working to become as familiar with that country as he is with Canada. “The politics and the history of the place are different,” he says. “Your journalistic antennae are misaligned. And I console myself with the thought that being Canadian isn’t just living in Canada. It’s exporting Canadian things to other societies. There are neat moments when I feel I’m bringing Canadian eyes to a story that I’m broadcasting to Americans.”

THALIA ASSURAS. Thalia Assuras caught ABC’s attention in early 1993, when, as an anchor for CTV’s Canada AM, she reported on the resignation of Brian Mulroney. She was the show’s main news reader and co-host of its weekend edition following stints at Global, Citytv and CBC.

The ABC call was a surprise. Unlike many colleagues, Assuras had never considered looking for work in the US. “They’re quite astounding,” she says of the ABC talent scouts. “They have tentacles everywhere. They happened to be watching, called me up and said, ‘Hey, we’d like to talk to you.’”

In March, Assuras made another move, this time to CBS’s new cable network, Eye on People, after three years anchoring ABC’s overnight newscast, the smart, irreverent and entertainingly quirky World News Now. She is developing a daily prime-time show for the cable channel that she’ll anchor while handling her regular reporting chores: long-form interviews plus field work — much like what she did at ABC, but with more editorial say.

“A journalist is a journalist is a journalist,” says Assuras, commenting on her varied responsibilities. “Your essential task is to gather information and communicate it. But there are major differences between Canadian and American networks, the main one being money.” Indeed, when it comes to things like facilities, equipment, satellite time and travel, there is no regard to cost.

“It’s hugely competitive here, which brings out the best and the worst in people. The focus of the stories is very much American. This is a world power; it sees the world through its own eyes. So much that happens in the world is related to the US, they can’t help it. You can go through a whole newscast here without one foreign story.” Would she return north? “You never close the door. I never expected to be here, and I don’t know where I’ll end up.”

MARINA KOLBE. Marina Kolbe (who is originally from Montreal, and fluent in English, French and Italian) can be seen on CNN’s main channel on an hourly basis, reporting on the financial situation from Wall Street. She started the job in January 1996, after five years with CBC and Newsworld, where she also did hourly business news updates in addition to working as a correspondent and anchor.

“With all of the problems in Canadian television, you have to think about the future,” Kolbe says of her move to CNN in New York. “I was working in Italy as a freelance reporter, and I had met people from CNN. Then, when they started the financial channel [CNNfn was launched the same month Kolbe started], they called me up.”

Along with its uncertain future, Kolbe says she was glad to leave other aspects of CBC’s corporate culture behind: “There’s a young culture here, and not all the union pressures. You can get things done. Here at CNN, unions don’t get in the way. I have no problem doing everything. And everyone does.” What some might see as pressure, Kolbe views as accountability. “Here, you’ve got to get your job done or you’re out.”

Kolbe’s job adds up to a total of 20 hourly “hits” for CNN, CNNfn and CNN International, seen in more than 200 countries and territories around the planet. Between all of her on-camera appearances, Kolbe and her producer are responsible for tracking the Dow Jones Industrial Average and gathering information and intelligence about its performance from investment wizards. “We’re both flying, working really hard to keep up with everything. You’re talking with people who move megabucks and they really know what’s happening.”

When she’s not working the phones or reporting on-camera, Kolbe occasionally trades e-mail with other Canadians who also work at CNN (Patricia Chew, Jonathan Mann and Brian Yasui, to name just a few), some expressing their utter relief at having escaped CBC when they did; “there but for the grace of God and/or Ted Turner.”

SHEILA MACVICAR. Sheila MacVicar is starting her sixth year as a London-based foreign correspondent with ABC News. She was hired just about the time the Gulf War was heating up, in 1990. Like Hilary Brown, MacVicar’s itinerary is similarly frenetic and far-flung, including — in just the last year — Bosnia, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Saudi Arabia, Moscow and back to Moscow again. “And in 1996 we were in a US presidential year, so this was a slow cycle for foreign news,” she says.

Two networks there approached MacVicar in 1986, when she was a foreign correspondent for CBC. She turned them down. But as the corporation’s future grew bleaker and MacVicar’s self-confidence grew, she rethought her earlier decision. “No one works at CBC for the money, let’s face it. You’re committed to an institution and its values. For me, the decision to leave was not a matter of the economic factor. It had more to do with the opportunities and what I saw happening at CBC.”

MacVicar has watched the BBC go through difficulties similar to those facing CBC, in the process remaking itself into a much stronger, smarter broadcaster. She’d like to see CBC do likewise, but acknowledges that six time zones and two official languages make that much tougher to do in Canada. “But CBC is a master at doing smart coverage — getting the best use out of their people and their limited resources.”

The biggest professional challenge in making the switch was trading a dispassionate professional distance — the hallmark of CBC reporting — for something more visceral and more involved. “Basically, here they want you to have the entire control room in tears.”

PATRICIA CHEW. Patricia Chew wanted an overseas posting anywhere but in the US. She is currently working for CNN as an anchor/correspondent in Hong Kong for CNNI (known as CNN International). That move began with a message on her voice mail in CBC’s documentary unit: “‘Hi — calling from CNN. Looking for someone for Hong Kong. You interested?’ I was delighted.” A deal allowing CNN and CBC the use of each other’s material meant that the people in Atlanta were well acquainted with Chew’s work. Still, adapting to CNN’s corporate culture required some adjustments. “This is a test of everything you’ve learned,” Chew says. “At CNNI, they don’t hire anchors, they hire journalists. They rely on you to use your judgment a lot. You will say to them, ‘This is a big story, it’s an important issue. We should do this.’ They’ll say, ‘OK. What do you need?’

“Leaving CBC was a wrench,” she adds. “I never wanted to leave; they’d been really good to me. But I have to say it is truly wonderful to work for a place that’s expanding instead of contracting.”

In her current slot, Chew anchors two newscasts on weeknights, hosts a weekend magazine show, which is called Inside Asia, and reports from the field — most recently in a half-hour special on the issues facing Hong Kong as it prepares for its hand-over to China. “This is the story of the decade, and I wouldn’t miss it for the world,” she says.

The Hong Kong posting is both a personal and professional homecoming. “I went to high school here, and the place was just thrumming,” says Chew. “There were the May-June riots, bombs going off; the Vietnam War was in full swing. There was a huge purge happening in mainland China — bodies were washing up on the beaches. I think it was then I decided, ‘I want to be a journalist.’ It was a very pivotal time in my life. It’s like a second home, and I think that gives it a special resonance for me.”